How Will Climate Change Affect New Jersey

On This Page:

On This Page:

- Overview

- Sea Level Rise

- Changes in Storm Surge and Atmospheric precipitation

- Coastal Water Temperature

- Coral Reefs and Shellfish

Overview

The coastline of the United States is highly populated. Approximately 25 one thousand thousand people alive in an area vulnerable to littoral flooding.[1][2] Coastal and ocean activities, such as marine transportation of goods, offshore energy drilling, resource extraction, fish cultivation, recreation, and tourism are integral to the nation's economy, generating 58% of the national gross domestic product (Gross domestic product).[2] Coastal areas are also home to species and habitats that provide many benefits to guild and natural ecosystems.

Click the image to run across a larger version. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects that sea level rise volition increase flooding in Charleston, South Carolina. Source: NOAA Coastal Services Center (2012)

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects that sea level rise volition increase flooding in Charleston, South Carolina. Source: NOAA Coastal Services Center (2012)

The impacts of climate change are probable to worsen problems that littoral areas already face. Confronting existing challenges that affect human being-fabricated infrastructure and coastal ecosystems, such as shoreline erosion, littoral flooding, and water pollution, is already a business organisation in many areas. Addressing the additional stress of climate change may require new approaches to managing land, water, waste, and ecosystems.

Meridian of Page

Ocean Level Rise

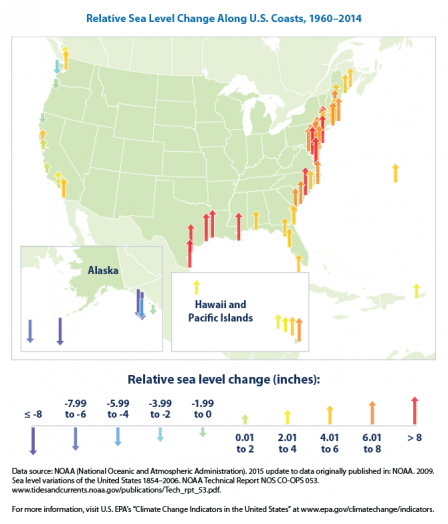

Click the image to view a larger version. Observed changes in sea level relative to land elevation in the United States between 1960 and 2014. Source: EPA (2015)

Observed changes in sea level relative to land elevation in the United States between 1960 and 2014. Source: EPA (2015)

Since 1901, global sea level has risen approximately 8 inches.[3] [4]

In a particular location, the change in sea level that is observed volition be affected by the increase in global sea level also equally land motion up or downwards. The movement of country tin be caused past subsiding coastal lands, oil and h2o extraction activities, melting ice, or tectonic motility. The terms "local" or "relative" sea level refer to both the global change in body of water level and the effects of land motion.

Where the land is sinking, the charge per unit of relative ocean level rise is larger than the global rate. Some of the fastest rates of relative sea level rising in the United States are occurring in areas where the land is sinking, including parts of the Gulf Coast. For example, coastal Louisiana has seen its relative sea level rise by eight inches or more in the last fifty years,[2] which is most twice the global rate. Subsiding country in the Chesapeake Bay area worsens the effects of relative sea level ascent, increasing the gamble of flooding in cities, inhabited islands, and tidal wetlands.[2]

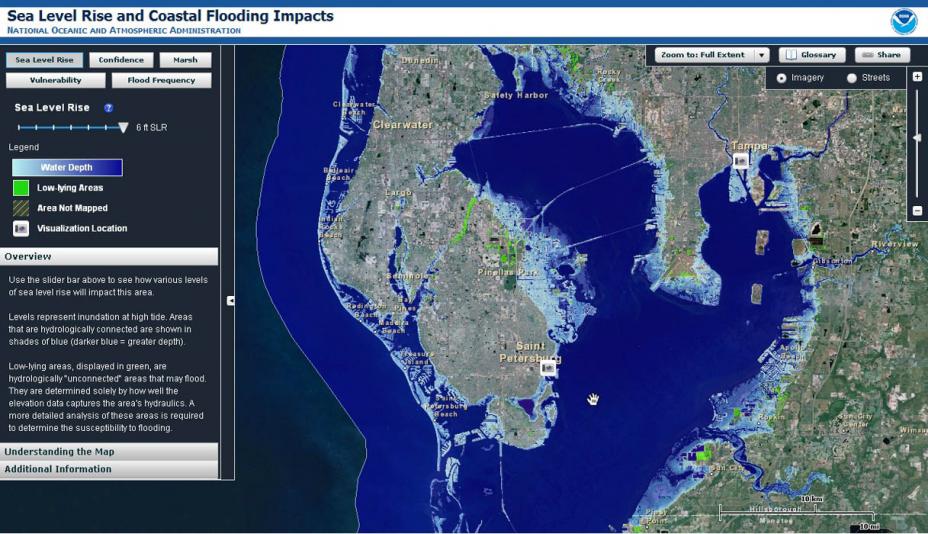

Sea Level Ascension and Coastal Flooding Impacts Viewer

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has adult a tool to visualize the potential impacts of sea level rise on coastal communities in the United States.

NOAA'southward sea level ascent and littoral flooding impacts viewer. Source: NOAA (2012)

NOAA'southward sea level ascent and littoral flooding impacts viewer. Source: NOAA (2012)

More often than not because of these differences in land motion, estimates of future relative sea level rise vary for different regions. Climate alter models project that global sea level rise volition advance in the 21st century. Models based on thermal expansion and ice cook estimate that global sea level is very likely to rise betwixt ane and 3 feet by the end of the century. Typically, these models do not, however, incorporate all of the possible responses of ice sheets to warmer temperatures, which could further raise sea level, simply is unlikely to add more than one foot.[2] [4][5]

For more data on recent and time to come ocean level rise, please visit the Science section.

Growing populations and development forth the coasts increase the vulnerability of coastal ecosystems to body of water level rise. Development can block the inland migration of wetlands in response of sea level rise, and alter the amount of sediment delivered to coastal areas and accelerate erosion. For example, littoral Louisiana lost approximately 2000 foursquare miles of wetlands in recent decades due to human alterations of the Mississippi River'due south sediment system and oil and h2o extraction that has acquired country to sink. As a result of these changes, wetlands do not receive enough sediment to go on up with ascent seas, and may no longer part as natural buffers to flooding.[vi]

Ascension sea level also increases the salinity of ground h2o and pushes salt h2o further upstream. College salinity tin can make water undrinkable without desalination, and harms many aquatic plants and animals.[two]

Top of Page

Impacts of Changes in Storm Surge and Precipitation

Littoral areas are likewise vulnerable to increases in the intensity of storm surge and heavy precipitation. Storm surges flood depression-lying areas, impairment holding, disrupt transportation systems, destroy habitat, and threaten human health and prophylactic. For instance, depression-lying areas of New York City, Long Island, and New Jersey were flooded past several feet of water by the tempest surge from Superstorm Sandy in 2012.[2] [5] Sea level rising could magnify the impacts of storms by raising the base on which storm surges build.[seven]

Climate change is likely to bring heavier rainfall to some littoral areas, which would also increment runoff and flooding. In addition, warmer temperatures in mountain areas could lead to more leap runoff due to melting of snow. In turn, increases in spring runoff may also threaten the health and quality of coastal waters. Some coastal areas, such as the Gulf of Mexico and Chesapeake Bay, are already experiencing "dead zones." Dead zones occur when state-based sources of pollution (e.g., agricultural fertilizers) contribute to algal blooms. When the algae sink and decompose, the process depletes the oxygen in the h2o. As increases in spring runoff bring more nitrogen, phosphorus, and other pollutants into coastal waters, many aquatic species could be threatened.[1]

Decreases in atmospheric precipitation could also increment the salinity of coastal waters. Droughts reduce fresh h2o input into tidal rivers and bays, which raises salinity in estuaries, and enables table salt h2o to mix further upstream.[2]

Top of Page

Impacts of Coastal Water Temperature

Coastal waters accept warmed during the last century, and are very likely to continue to warm in the 21st century [2][5], potentially past as much as 4 to 8°F.[eight] This warming may pb to large changes in coastal ecosystems, affecting species that inhabit these areas.

Warming coastal waters cause suitable habitats of temperature-sensitive species to shift poleward. Some areas have recently seen range shifts in both warm- and common cold-h2o fish and other marine species. Pollock, halibut, rock sole, and snow crab in Alaska and mangrove trees in Florida are a few of the species whose habitats take already begun to shift.[ii] [5] Suitable habitats of other species may too shift, because they cannot compete for limited resources with the southern species that are moving n.[1]

For more information on climate modify impacts on species, visit the Ecosystems page.

Top of Page

Climate Prepare Estuaries Plan

Estuaries are particularly sensitive to many projected impacts of climate change, including erosion from rising seas, changes in storms frequency and intensity, and the corporeality of precipitation. EPA's Climate Ready Estuaries plan works with National Estuary Programs and other coastal managers to:

Estuaries are particularly sensitive to many projected impacts of climate change, including erosion from rising seas, changes in storms frequency and intensity, and the corporeality of precipitation. EPA's Climate Ready Estuaries plan works with National Estuary Programs and other coastal managers to:

- Appraise climatic change vulnerabilities.

- Appoint and educate stakeholders.

- Develop and implement adaptation strategies.

- Share lessons learned with other coastal managers.

The Climate Set up Estuaries website provides resources for estuaries and coastal programs that are interested in learning more than nigh climate change impacts and adaptation.

To larn more than about estuaries, visit the National Estuaries Program web folio.

Impacts to Coral Reefs and Shellfish

Bleached brain coral. Source: NOAA College ocean surface temperatures increase the risks of coral bleaching, which can lead to coral death and the loss of critical habitat for other species.[2] The ascension concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere has increased the assimilation of COii in the ocean, which subsequently makes the oceans more acidic. This trend is very likely to continue in the coming decades. A more than acidic ocean adversely affects the health of many marine species, including plankton, mollusks, and other shellfish. In particular, corals tin can exist very sensitive to rising acidity, as information technology is hard for them to create and maintain the skeletal structures needed for their back up and protection. Corals in the Florida Keys, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and other U.S. territories are probable to experience substantial losses if CO2 concentrations in the temper continue to rise at their current rate.[ii]

Bleached brain coral. Source: NOAA College ocean surface temperatures increase the risks of coral bleaching, which can lead to coral death and the loss of critical habitat for other species.[2] The ascension concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere has increased the assimilation of COii in the ocean, which subsequently makes the oceans more acidic. This trend is very likely to continue in the coming decades. A more than acidic ocean adversely affects the health of many marine species, including plankton, mollusks, and other shellfish. In particular, corals tin can exist very sensitive to rising acidity, as information technology is hard for them to create and maintain the skeletal structures needed for their back up and protection. Corals in the Florida Keys, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and other U.S. territories are probable to experience substantial losses if CO2 concentrations in the temper continue to rise at their current rate.[ii]

Top of Page

References

[1] FEMA (2008). Littoral AE Zone and VE Zone Demographics Study and Main Frontal Dune Written report to Support the NFIP. Washington, DC: Federal Emergency Management Agency Technical Report, 98p.

[2]USGCRP (2014).Moser, Southward. C., M. A. Davidson, P. Kirshen, P. Mulvaney, J. F. Murley, J. East. Neumann, L. Petes, and D. Reed, 2014: Ch. 25: Littoral Zone Development and Ecosystems. Climatic change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Every bitsessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.South. Global Change Enquiry Program, , 579-618.

[3] USGCRP (2014). Walsh, J., D. Wuebbles, K. Hayhoe, J. Kossin, K. Kunkel, K. Stephens, P. Thorne, R. Vose, M. Wehner, J. Willis, D. Anderson, S. Doney, R. Feely, P. Hennon, V. Kharin, T. Knutson, F. Landerer, T. Lenton, J. Kennedy, and R. Somerville.Ch. 2: Our Irresolute Climate. Climate Change Impacts in the Us: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and 1000. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Plan, nineteen-67.

[iv] IPCC (2013). Rhein, K., S.R. Rintoul, S. Aoki, E. Campos, D. Chambers, R.A. Feely, S. Gulev, 1000.C. Johnson, S.A. Josey, A. Kostianoy, C. Mauritzen, D. Roemmich, 50.D. Talley and F. Wang. Observations: Sea. In:Climate change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Study of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, One thousand.-Thou. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.1000. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, Five. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, U.s.a..

[5] IPCC (2014). Wong, P.P., I.J. Losada, J. Gattuso, J. Hinkel, A. Khattabi, Yard. McInnes, Y. Saito, and A Sallenger. Coastal systems and depression-lying areas. In: Climate Modify 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the 5th Cess Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change [Field, C.B., 5.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, Chiliad.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.East. Bilir, Grand. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.Due north. Levy, Due south. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L.White (eds.)]. Cambridge Academy Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, United states.

[half-dozen] CCSP (2008). Impacts of Climate Change and Variability on Transportation Systems and Infrastructure: Gulf Coast Study, Phase I. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Alter Research. Savonis, Yard. J., Five.R. Burkett, and J.R. Potter (eds.). Section of Transportation, Washington, DC, Us, 445 pp.

[7] NRC (2010). Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change. National Research Council. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, The states.

[viii] USGCRP (2009).Global Climate Modify Impacts in the The states, Coasts. Karl, T.R., J.M. Melillo, and T.C. Peterson (eds.). United States Global Modify Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

Superlative of Folio

Source: https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/climate-impacts/climate-impacts-coastal-areas_.html

Posted by: russelldaming.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Will Climate Change Affect New Jersey"

Post a Comment